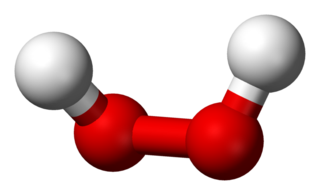

Mix two hydrogens with two oxygens and, voila — hydrogen peroxide.

The Third Circuit took a torque wrench today to the standards for class certification under Rule 23(b)(3). The tightening may portend mini-trials — and perhaps big ones, too – on whether or not a price-fixing case meets the requirements of the rule. In re Hydrogen Peroxide Antitrust Litig., No. 07-1689 (3d Cir. Dec. 30, 2008).

The litigation involved a claim that manufacturers of hydrogen peroxide, sodium percarbonate, and sodium perborate conspired to fix prices on those chemicals during the period from January 1, 1994 through January 5, 2005. The district court denied motions to dismiss and, after "extensive" discovery, granted a motion to certify a domestic purchaser class.

The Third Circuit granted discretionary review of the certification order under Rule 23(f). And it vacated the order and remanded for reconsideration of class treatment under a more stringent test than the one the district court applied. The panel summarized thus:

In deciding whether to certify a class under Fed. R. Civ. P. 23, the district court must make whatever factual and legal inquiries are necessary and must consider all relevant evidence and arguments presented by the parties.

See Newton v. Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc.

, 259 F.3d 154, 166, 167 (3d Cir. 2001) (citing Szabo v. Bridgeport Machs., Inc., 249 F.3d 672, 676 (7th Cir. 2001); Manual for Complex Litigation (Third) § 30.1 (1995)). In this appeal, we clarify three key aspects of class certification procedure. First, the decision to certify a class calls for findings by the court, not merely a “threshold showing” by a party, that each requirement of Rule 23 is met. Factual determinations supporting Rule 23 findings must be made by a preponderance of the evidence. Second, the court must resolve all factual or legal disputes relevant to class certification, even if they overlap with the merits—including disputes touching on elements of the cause of action. Third, the court’s obligation to consider all relevant evidence and arguments extends to expert testimony, whether offered by a party seeking class certification or by a party opposing it.

In re Hydrogen Peroxide, slip op. at 5.

The guts of the opinion deals with what class action wags call "the battle of the experts". The district court's sin, the panel held, consisted in giving a pass to the plaintiffs-side expert's opinions on whether the class could prove "common impact" of the conspiracy on all class members (i.e., that all class members paid a higher price than they would have absent collusion).

The court noted that both sides presented expert opinions and highlighted that the district court chose not to determine which side's evidence carried more persuasive force. A "threshold showing" by the plaintiffs' expert — even one that withstands a Daubert challenge to admissibility – won't do. Instead:

Like any evidence, admissible expert opinion may persuade its audience, or it may not. This point is especially important to bear in mind when a party opposing certification offers expert opinion. The district court may be persuaded by the testimony of either (or neither) party’s expert with respect to whether a certification requirement is met. Weighing conflicting expert testimony at the certification stage is not only permissible; it may be integral to the rigorous analysis Rule 23 demands.

In re Hydrogen Peroxide, slip op. at 46.

Blawgletter imagines that the trouble may have stemmed from the plaintiffs' expansive class definition, both temporally (an 11-year period) and by product (all grades and concentrations). The court tersely — and wryly? — implied as much in a footnote, observing that "[t]he current record suggests it may be possible to overcome some obstacles to class certification by shortening the class period or by fashioning sub-classes. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(c)(5)." In re Hydrogen Peroxide, slip op. at 51.